To weather the challenges of modern geopolitics, countries must take great care in pursuing their national interest in the face of ever-changing circumstances, writes Vadym Ivchenko.

This sentiment rings especially true for smaller, less wealthy nations precariously positioned in unstable regions of the world. Such states lack the luxury of adopting a lackadaisical approach, existing without the assured stability of great powers. No country, perhaps, better illustrates this desperate need more than Ukraine, ravaged by war and suffering from a series of failed economic reforms. Does this promising, yet struggling country have the vision necessary to realise its full potential?

The Author, Vadym Ivchenko, is a Member of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (Ukrainian Parliament), elected in 2014.

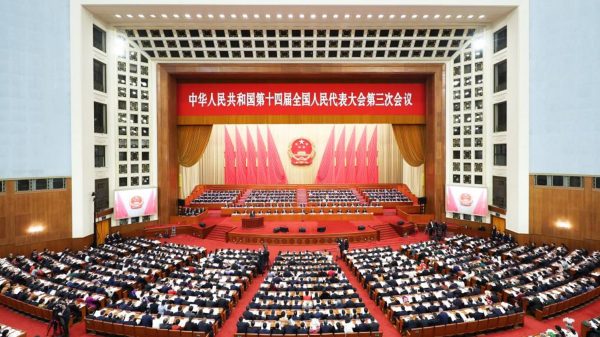

Let’s consider the issue from the angle that most greatly impacts everyday Ukrainians, namely the topic of land and land reform. Interestingly, for such a contentious regulatory question, it’s a rather new one. Last March, despite fierce opposition from farmers’ organisations and other concerned groups, Ukraine’s parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, pushed through a majority vote lifting the moratorium on the alienation of agricultural land. In layman’s terms, legislation to introduce a so-called land market.

As they typically do, these reforms came along with their fair share of promises, most prominently, that of an investment boom in the agricultural sector, an irresistible prospect for a largely agrarian nation. Yet, these promises, as they typically are, were empty. They were right on one count, however. The market undoubtedly reacted.

With farmers saving the last of their hard-earned money to buy back their land, a precipitous plummet in investment has rocked the nation ever since. By 2020’s end, Ukrainian domestic investment plunged by more than 40%. In real terms, the nation witnessed the evaporation of around $2 billion.

These farmers’ endeavour to buy back their land at all costs, while understandable, may yet carry disastrous consequences. As a result, there has been an investment drought in a wide range of technologies crucial to the overall health of the nation’s agricultural industry, such as expanded production, soil fertility restoration, organic farming, and the purchase of biogas plants. Instead, land users are utilising plots for the sole purpose of generating quick profits, preferring to sow oil seeds. This practice, however, results in the unfortunate repercussion of bleeding Ukraine’s rich black soil deposits.

Scientists have begun sounding the alarm of this catastrophic decrease in the soil’s humus levels, and, despite their involvement, have alarmingly observed that the decline is accelerating! This could spell disaster for Ukraine, as the country has a rate of agricultural development far exceeding most of the world. For perspective, compared to European countries, whose arable land comprises 30-32% of their total area, Ukrainian arable land exceeds 65% of its total geography.

Worst of all, perhaps, is that local farmers still fall spectacularly short of the funds necessary to buy back their land in full. In fact, the full might of the Ukrainian banking system still falls well short of the mark. Astoundingly, the land’s price is considerably greater than the funds held by the entire national economy, including even its financial sector. In 2020, the money supply in circulation amounted to UAH 1.7 trillion, while expert estimates value the land at more than UAH 1.9 trillion, 15% higher than Ukraine’s entire money supply. Therefore, a substantial infusion of funds by foreign investors is both necessary and expected.

In the face of these circumstances, Ukraine has been placed in a strenuous position, becoming the battleground for several global powers, all while seeking to maintain its sovereignty. Chiefly, the country must wrestle with the question of allowing for the purchase of precious agricultural land by the representatives of other nation-states. This issue is yet to be decided, as Ukrainian law currently forbids the sale of land to foreigners, and amending this status quo can only be attempted after the All-Ukrainian referendum.

Another quirk of Ukrainian law is that a change in a land plot’s ownership does not terminate its original contract, meaning that if a shareholder was to sell his land, the leasing party maintains the right to lease the property until the contract expires. This hiccup is exacerbated by the fact that a majority of such contracts have a 10-year lifespan. Thus, potential investors are faced with the prospect that, even upon purchasing lucrative property, they will be unable to utilise it for many years. This real estate climate drives down prices, as the only eager buyers are either farmers seeking to cultivate the land or long-term investors.

The question of foreign investment remains.

Even now, although preventative legislation exists, there is a de-facto foreign presence in the Ukrainian agricultural sector. The amount of land leased by foreign investors is now roughly equal to the area of Switzerland, or 4 million hectares to be exact. American investors own NCH Capital, the third largest agricultural holding in the country, spanning 400,000 hectares. Other countries are also getting in on the action, with a Saudi Arabian investment fund procuring more than 270 thousand hectares.

There are several motivations for foreign parties from across the world to invest in Ukrainian black soil. Let’s take some time to consider a few possible international directions:

China:

In 2013, the press was alerted to a possible purchase of 100,000 hectares of Ukrainian land by the state-owned Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps, or the XPCC. Although these reports were hastily denied by official representatives, they did confirm the existence of an agreement between the XPCC and the Ukrainian agricultural holding KSG Agro regarding cooperation on an area of that exact size in the Dnipropetrovsk region. Such steps are likely just trial balloons that, if deemed profitable, will lay the groundwork for various forms of continued cooperation and consolidation on Ukrainian soil.

Saudi Arabia:

Despite their previously mentioned purchase of 270 thousand hectares, the country has only recently begun investing in Ukraine. Saudi Arabia views Ukraine as one of the lucrative Black Sea Basin countries, yet refrains from becoming overcommitted, looking to switch to nearby countries such as Romania and Bulgaria, which also have decent soil, if too many difficulties arise.

Turkey:

Turkey’s Ambassador to Ukraine, Yağmur Ahmet Güldere, has expressed that his country was interested in buying land in Ukraine. Similarly, Turkish businessmen see Ukrainian farmland as a promising source of profit and investment infusions, closely following the Ukrainian reform process and awaiting their opportunity.

Europe:

Several representatives of the European community have repeatedly declared interest in purchasing tracts of agricultural land in Ukraine. German MEP Michael Gahler, for instance, noted that legalising foreign investment in the agricultural sector, especially from diplomatic allies, would be a positive signal for Ukraine’s investment climate. Still, Ukrainian politicians have reason for concern, citing the historical example of Latvia in the 1990s, where European investors swooped in to capitalise on the newly formed market’s cheap rates. More than 30 years later, Latvia is still reaping the consequences, with local farmers being forced to rent from foreign landowners.

It cannot be ignored, however, that the EU is one of Ukraine’s largest providers of foreign aid, spending more than €13 billion, or about $14.2 billion, in loans and €2 billion, or $2.2 billion, in grants from 2014 to 2019. This, naturally, means that any changes to Ukraine’s markets, especially its real estate market, are of great concern to Europe, as the country’s main financial creditor.

“The EU is in a precarious international position, possessing a vested interest in Ukrainian regional policy as a consequence of being the nation’s largest creditor. However, Europe must be wary of larger players looming in the Ukrainian real estate market, namely, the inevitable clash between American and Russian spheres of influence.” — Pasquale Palikastro, Professor of the Department of Constitutional Law and European Integration

USA:

As mentioned before, the American Pension Fund, also known as NCH Capital, currently rents about 480,000 hectares of land in the Sumy, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, Poltava, Vinnytsia, Zhytomyr, Khmelnytskyi, Ternopil, Rivne, Volyn, and Lviv regions. Furthermore, there are plans to expand into the fields of crop production and animal husbandry. The current strategy is to rent small plots of land, combining them into larger farms. Thus, if Ukraine’s moratorium on foreign land purchases was to end, NCH Capital would naturally prioritise the purchase of its already leased plots.

The much-needed context, however, is that the United States has been long guided by former National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski’s thesis, originally put forward in 1994, who justified America’s engagement with newly-independent Ukraine by arguing that it would prevent the rise of a new Russian empire by bolstering regional and global security. “It cannot be stressed strongly enough that without Ukraine,” Brzezinski said, “Russia ceases to be an empire, but with Ukraine suborned and then subordinated, Russia automatically becomes an empire”.

Which, of course, brings us to Russia.

Russia:

It’s fair to say that Russia has been historically interested in Ukrainian agricultural land. This preoccupation is not about making a profit, but rather a political one. Land can be utilised for a variety of strategic purposes, with one of Russia’s favourite tactics being to use its purchased property for social manipulation. With the country’s aggression towards Ukraine in 2014, however, Russian businesses have become limited in their access to Ukrainian land. Legal measures even bar Russian citizens from co-founding Ukrainian companies seeking to buy agricultural land, with offending parties being subject to forfeiture. Thus, Russian capital must enter the Ukrainian market under the guise of another country’s investment.

In conclusion, one thing is clear; Many foreign actors are eagerly awaiting involvement in the Ukrainian land market. Potential investors face the prospect of many roadblocks, including the public’s tolerance for corruption, volatile legislation, ambiguous property rights, suspect law enforcement agencies, ineffective trust-busting, an ineffectual judicial system, as well as political and economic instability. Yet, despite these impediments, the desire to take advantage of Ukraine’s wide tracts and lucrative soil is more than enough to lure the boldest of the bunch.

The Author, Vadym Ivchenko, is a Member of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine (Ukrainian Parliament), elected in 2014.