High Representative Josep Borrell has warned of the growing dangers facing the EU and its allies in world of “much more confrontation and much less cooperation”. “I see a world much more fragmented. I see a world where rules are not being adhered to”, he said in a wide-ranging speech at Oxford University. The location was also post-Brexit gesture of friendship towards the United Kingdom, “a close friend and a close partner”. He called for close cooperation based on shared vales and “converging interests on almost all geopolitical questions”, writes Political Editor Nick Powell.

In his Dahrendorf lecture at Saint Antony’s College, Oxford, Josep Borrell described a world that is going in the wrong direction. “I see more confrontation and less cooperation. This has been a growing trend in the last years: much more confrontation and much less cooperation.

“I see a world much more fragmented. I see a world where rules are not being adhered to. I see more polarity, and less multilateralism. I see how dependencies become weapons.

“I see the international system, that we were accustomed to after the Cold War, no longer exists. America has lost its status of a hegemon. And the post-1945 multilateral order is losing ground”.

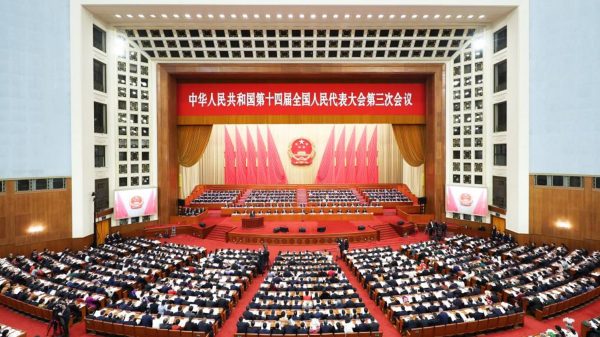

He said the rise of China to super-power status is an economic achievement “unique in the history of humankind”, making it a rival for both the European Union and the United States, “not just in manufacturing cheap goods, but also as a military power, at the forefront of the technological development and building the technologies that will shape our future”.

Of China’s ‘friendship without limits’ with Russia, he dryly observed that all friendships have limits but nevertheless said it signalled what he called “a growing alignment of the authoritarian regimes in front of democracies”.

Of the emerging middle powers, such as India, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, South Africa and Türkiye, he said they are becoming important actors but with “very few common features, except the desire for getting more status and a stronger voice in the world, as well as greater benefits for their own development.

“In order to achieve this, they are maximising their autonomy, not willing to take sides, hedging one side or the other depending on the moment, depending on the question. They do not want to choose camps and we should not push them to choose camps”.

Closer to home, “we Europeans wanted to create in our neighbourhood a ring of friends. Instead of that, what we have today is a ring of fire. A ring of fire coming from the Sahel to the Middle East, the Caucasus and now in the battlefields of Ukraine”.

And the High Representative observed that when he took up his post, there were no wars in Europe and its neighbourhood, now “there are two wars where people are fighting for the land. This shows that geography is back. We were told that globalisation had made geography irrelevant, but no. Most of the conflicts in our neighbourhood are related to land, they are territorial. A land that has been promised to two people, in the case of Palestine, and a land at the crossroads of two worlds, in the case of Ukraine”.

There are also challenges caused by climate change, technological change and rapid demographic change. “And when I am talking about demographic balances, I am talking about migration, in particular in Africa where 25% of the world will be living in 2050. In 2050, one out of four human beings will be living in Africa. And at the same time, we see inequalities growing, democracies declining and freedoms at risk.

“This is what I see. It is not very nice, I know. In this landscape, the role of the European Union, and the role of the United Kingdom, is to be defined” he continued. “Well, okay. What do we need to do?

“First, we need a clear assessment of the dangers of Russia – Russia considered as the most existential threat to Europe. Maybe not everybody in the European Council agrees with that, but the majority is behind this idea. Russia is an existential threat for us, and we have to have a clear-eyed assessment of this risk. Second, we have to work on principles, on cooperation and on strength.

“But first, about Russia. Under Putin’s leadership, Russia has returned to the imperialist understanding of the world. Imperial Russia from the Tsar times and the Soviet empire times have been rehabilitated by Putin dreaming of a former size and influence. It was Georgia in 2008. It was Crimea in 2014. We did not see, or we did not want to see, the evolution of Russia under Putin’s watch”.

Despite Vladimir Putin’s clear warnings, Josep Borrell argued that the EU and its allies believed that interdependence would bring political convergence. “What the Germans call “Wandel durch Handel” [change through trade]. This would bring political change, in Russia and even in China.

“Well, this has been proven wrong. It has not happened. Faced with the Russian authoritarianism, interdependence did not bring peace. On the contrary, it turned into dependence, in particular on fossil fuels, and later, this dependence became a weapon.

“Today, Putin is an existential threat to all of us. If Putin succeeds in Ukraine, he will not stop there. The prospect of having in Kyiv a puppet government like the one in Belarus, and the Russian troops on the Polish border, and Russia controlling 44% of the world grain market is something that Europeans should be aware of”.

He welcomed the French president’s conversion from dove to hawk. “Even President Macron, who at the beginning said, ‘Il ne faut pas humilier la Russie’ [‘Russia must not be humiliated’]. Now, he is one of the voices which is warning more about the global consequences of a Russian victory.

“But I know that not everybody in the European Union shares this assessment. And some European Council’s members say, ‘well no, Russia is not an existential threat. At least not for me. I consider Russia a good friend’. There are not many, but there are some”.

The High Representative confessed that on the eve of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, with 150,000 Russian troops massing on the border, he could not tell the Ukrainian Prime Minister if Europe would provide his country with weapons “because the European Union had never provided arms to a country at war. But then, the invasion came and happily, our answer was remarkable and very much united in order to provide Ukraine with the military capacity they need to resist”.

He acknowledged that the United Kingdom had acted decisively before the European Union stepped up its contribution. “At the beginning, we were talking about providing helmets, and now we are providing F-16 [fighter jets]”. But even now, when “Putin sees the whole West as an adversary, … Ukraine is resisting in difficult circumstances, overcoming the fact that the United States and the European Union have not been supplying everything they need to continue the fight.

With the Israel-Hamas War also raging, “we have two wars. And we, Europeans, are not prepared for the harshness of the world … do we understand the gravity of the moment? I have my doubts”.

In describing how Europe should set its future foreign policy course, Josep Borrell argued that the EU should start with its principles. “Principles are important because we say that the European Union is a Union of values. That is what is being said in our treaties.

“Then, there are the principles enshrined in the Charter of the United Nations, to put a limit to the actions of the stronger … those principles outlawed ‘the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state’.

Then, there is International Humanitarian Law to try to regulate how wars are fought and safeguard the protection of civilians. These principles should be the best safeguard against the normalisation of the use of force that we see all over the world.

“I know, however, that to be able to rally the world around those principles, we need to show that we Europeans respect them always and everywhere. Is that what we are doing? Well, not to the extent we should. And for Europe, this is a problem.

“Wherever I go, I find myself confronted with the accusation of double standards. I used to say to my ambassadors that diplomacy is the art of managing double standards.

“What is now happening in Gaza has portrayed Europe in a way that many people simply do not understand. They saw our quick engagement and decisiveness in supporting Ukraine and wonder about the way we approach what is happening in Palestine”.

He warned of the perception that civilian lives in Ukraine are valued more highly than those in Gaza, “where more than 34,000 are dead, most others displaced, children are starving, and the humanitarian support obstructed”. He said that there is also a perception that Europe cares less about Israel’s violation of United Nations Security Council resolutions declaring its settlements on the West Bank illegal, than about Russia’s violation of resolutions on Ukraine.

“The principles that we put in place after the Second World War are a pillar of peace. But this requires that we are coherent in our language. If we call something a ‘war crime’ in one place, we need to call it by the same name when it happens anywhere else.

Josep Borrell commented that, in the end, there is no substitute for trust and cooperation. “But in a world where dependencies are increasingly weaponised, trust is in short supply. This brings the risk of decoupling with large parts of the world. Decoupling on technology, decoupling on trade, decoupling on values.

“There are more and more transactional relationships, but less rules and less cooperation. But the great challenges of the world – climate change, technologies, demographic change, inequalities – require more cooperation, not less cooperation.

So, he reasoned, excessive dependencies need to be reduced and trade links diversified but cooperation with the European Union’s “close friends” need to be deepened. “The United Kingdom is a close friend and a close partner. We share the same values. We have converging interests on almost all geopolitical questions. In any area where we can cooperate, it would be good for both of us”.

But healing the scars of Brexit is not enough. “If I was only talking with people who share the same values, I would stop working at midday. No, there are many people around the world [with] whom I do not share the same values or have contradictory interests. In spite of that, I have to look for ways of cooperating. This is the case of China.

“Then, we have to have a look at why the world is feeling some resentment about us. Yes, there is a feeling of resentment because people believe that there are different responsibilities. Let me cite only two of them.

“First, climate change. We, Europeans, have produced about 25% of all cumulated global CO2 emissions since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. [Sub-Saharan] Africa 3%, Latin America 3%. Sub-Saharan Africans and South Americans [have] almost nothing of the responsibility, and they share the most important and damaging consequences.

“So, when we talk about fighting climate change, we have to understand their views and the feeling that this is a problem that someone has created, and others pay the consequences. And the only possible answer is to provide more resources in order to face this problem.

The money, he said, should come from tackling what he called “fiscal injustice”. He called for the effective taxation of multinational corporations and the wealth of the world’s richest individuals. “This could provide the amount of money required to face climate change, which is considered an existential threat for humanity.

“The other reason for resentment are vaccines. When the pandemic came, and it was a matter of life or death, in December 2021 rich countries had already used 150 doses of vaccines per 100 inhabitants. 150 per 100 inhabitants. Lower income countries had just seven. We had 150, they had seven. And they remember that.

The High Representative concluded by talking about “the security side” of his job. “There is nothing that authoritarian regimes admire [as] much as strength. They like strength. And there is nothing for which they have less respect than weakness. If they perceive you as a weak actor, they will act accordingly. So, let’s try strength when talking with authoritarian people”.

He said it is a lesson that Europe had forgotten. “Maybe because we had been relying on the security umbrella of the United States. But this umbrella may not be open forever, and I believe that we cannot make our security dependent on the US elections every four years.

“So, we have to develop more our Security and Defence policy. I did not expect this part of my portfolio to take so much time and effort, but this is the way it is. We have to increase our defence capabilities and to build a strong European pillar inside NATO”.

He recalled how in the past talk of strengthening Europe’s collective defence was portrayed as undermining NATO. He did not point out that when the United Kingdom was a member state, the UK had firmly resisted the EU developing a military role. Instead, he was reaching out to the British.

“I think that the European Pillar of NATO has to be understood not from the point of view of the European Union alone, but from the geographical approach of Europe as a space which is bigger than the European Union. Not only from an institutional point of view – the 27- but from the point of view of the people who share what it is to be ‘European’.

“You are the United Kingdom, you left the European Union, but you are still part of Europe. And there are other people in Europe who are not part of the European Union, because they never wanted to be, like Norway, or they decided to stop being, as you, or they are still queuing to become members of the European Union. So, look at that security issue from a geographical perspective, not only an institutional one.

“And I think that there, in Security and Defence, we can have with the United Kingdom a stronger relation. We can build more because this is a pure intergovernmental policy inside the European Union. It should not be difficult to expand the bilateral treaties that we already have – like France with the United Kingdom, the Lancaster House Treaties – in order to make security an integral part of a better and stronger cooperation”.