As President Trump leaves the UK on the final day of the US state visit, what can we say we have learned from the last three days?

1. We are all getting used to Donald Trump

Whisper it quietly, but the capacity of the president to shock appears to be waning.

His visit resulted in much diplomatic carnage – the row with the mayor of London, Sadiq Khan; the pre-trip newspaper interviews advising on Brexit – but little seemed unexpected, as if Mr Trump was following a script with which we are now familiar.

There were the usual half-lies – the numbers protesting against his visit, about the extent of US-UK trade. There were the abrupt policy changes over whether or not the NHS would be involved in any future trade deal.

And there was the unapologetic advice about who our next prime minister should be, and what policy he or she should adopt over Brexit. But few appeared to be surprised by this.

People will continue to approve or disapprove of Mr Trump, depending on their viewpoint, but somehow the phenomenon that is Trumpism has become normal.

There were fewer protesters on the streets than last time.

The president, in turn, showed he could do modest, conducting a news conference with less bombast than usual where he praised Theresa May’s handling of Brexit.

He even managed to get through an entire day with the royal family without breaking protocol.

This visit seemed to show that for all the reservations some may feel, Britain is beginning to realise that Mr Trump is here to stay and it had better get used to him.

2. Britain can still put on a good show

British diplomats can hardly contain their relief and pleasure that the state visit went off with hardly a foot wrong.

“We showed we can still do it,” one told me.

The marching bands, the scarlet Grenadiers, the grandeur of the state banquet, the pomp, the pageantry and the royals, the royals! One senior official described the Queen as “our secret weapon”.

She is clearly one of the few people in the world who can inspire awe in President Trump: the sheer weight of her experience, longevity and acquaintance with eleven of his predecessors placing a lid on the braggadocio – at least for a moment or two.

Only she could have got away with using her banquet speech to deliver a firm message about the importance of the post-war international institutions that Mr Trump distrusts.

This was followed by a successful piece of diplomacy by the UK in getting the president to sign up to a joint D-Day proclamation with 15 other countries in favour of democracy, tolerance and the rule of law.

The aim was to use the occasion once again to remind Mr Trump of the importance of the international rules-based order and the crucial role the transatlantic relationship has played in that.

But for all the backslapping among Britain’s diplomats, there is still the risk that the success of the state visit and D-Day commemorations is used to cover up the UK’s relative weakness, the vain hope that a display of ceremonial prowess with echoes of past military glory can somehow correct the international damage the Brexit debate has inflicted on Britain’s reputation overseas.

3. D-Day holds a special place in our nation’s story…

…but will it be seen as a high-water mark for the special relationship?

At the start of the week British officials emphasised that the D-Day commemorations were the thing that mattered and that the long-delayed state visit was happening only because of the anniversary.

It would be a moment that really mattered – a reminder of the shared sacrifice that formed the foundation of the US-UK relationship.

The danger is that the history and the memories simply put in sharp focus the realisation that the world has moved on, that we are now in a new century where the transatlantic relationship is less central than before.

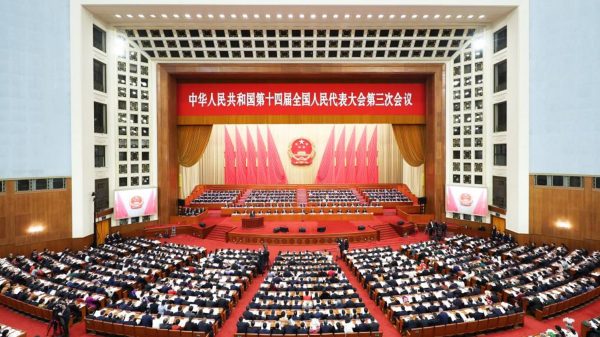

The focus now is on China and the new bipolar world. The UK has used this visit to remind the president of the importance of the transatlantic relationship, something Britain will need even more once it leaves the European Union.

But Mr Trump has given no evidence that his transactional, bilateral view of world affairs has changed, and that alliances are based not on past nostalgia but current interests. He made it clear that future trade talks with Britain would be hard.

He had no compunction in dismissing Jeremy Corbyn as a “negative force”, a man who as leader of the opposition could one day face him across the table in Downing Street.

It was noticeable, too, how many Conservative leadership contenders were willing to challenge openly Mr Trump’s promise – since revoked – to include the NHS in any future trade deal.

In other words, for all the talk of a special relationship, our future prime minister (whoever he or she will be) was quite happy to define themselves against the US president, even when Mr Trump was in Britain as an honoured guest of the Queen.

4. There was no great row over Huawei

Ahead of the state visit, there was much commentary suggesting there would be a row over Britain’s attitude towards the Chinese telecoms giant.

The US believes the firm is too close to the Chinese state.

And when the UK suggested it might be possible for Huawei to provide part of its future 5G phone network, there were grim warnings that the US might as a result restrict the intelligence it shares with Britain.

Yet this seems to have been the dog that did not bark over the last few days.

President Trump declared that “we are going to be able to work out any differences” and “we will have no problem with that.” So what reassured him? British officials deny that any decision has been made, let alone communicated to Mr Trump.

But clearly the UK’s promise that the security of its intelligence network will be paramount in any decision has gone a long way to take the heat out of this row.

And the reason this matters is because intelligence is a core element of the UK-US relationship, and any potential threat to that relationship would matter.

We should not forget that only recently Mr Trump repeated his claim that British intelligence agencies spied on his election campaign in 2016.

5. Donald Trump has moved his focus beyond Theresa May

Theresa May is prime minister and will remain so until such time that the Conservative party elects her successor at the end of July.

Yet her imminent departure hung over this visit like a thin mist.

Donald Trump felt able to joke about it, telling her publicly: “I don’t know exactly what your timing is but stick around, let’s do this (trade) deal”.

The president appeared to spend more time alone with Conservative leadership contenders than he did with the prime minister, seeing Jeremy Hunt and Michael Gove and holding a 20 minute phone call with Boris Johnson.

Media playback is unsupported on your device

Mr Trump also met other Brexiteer politicians such as Brexit party leader Nigel Farage and the former Conservative cabinet ministers Iain Duncan Smith and Owen Paterson.

During his news conference, Mr Trump felt able to praise both Mr Johnson and Mr Hunt, and even cheekily asked the foreign secretary whether Mr Gove might make a good prime minister.

On one level this was extraordinary, an astonishingly rude intervention in the domestic politics of another country.

But Mrs May is such a lame duck that Mr Trump got away with it.

She, in turn, felt more able to be explicit about her differences with the president, whether on Iran or China, warning him about the benefits of “cooperation and compromise”.

But Donald Trump knows that Britain’s approach to Brexit, trade and China will be decided by Mrs May’s successor, and neither side could disguise the fact.